|

Driving up to Brandon and Marie Hill's conservation food forest farm, in the farthest reaches of Northern Baltimore County, the rain came down in whispers and in sheets, nothing in between. Brandon's directions guided me to his parents' home on Bond Road, the home where he grew up. I drove down a long gravel road, past two wet and curious flea-bitten grey horses standing in a small field.

Brandon asked me to meet him in the driveway of his mom and dad's small cream rancher because he said his driveway was "treacherous." He was there in an army-issue green gator. He plopped my writing bag in the open back alongside a pair of tall rubber muck boots and the rash of things every farmer carries because you never know what will need doing. I climbed onto the bench seat.

The rain was steady, wetting my face as we set out down the long, narrow track, nearly invisible in the tall grass. Brandon said, "I'm going to show you everything." We were driving in what had been a cornfield the previous year, and now, he said, grinning, "it is grown up in a tall fescue, cover now; next year, food." Soon, "it will be in native Maryland grasses, and maybe," he said, "maybe, the pheasants can come back."

The first thing Brandon showed me was a chestnut orchard. Chestnuts, a revered tree all through the Appalachians for the food it provided and for its strong, beautiful wood, was sickened by a blight that began in the early 1900s. Chestnut trees were all but extinct by the 1930's, despite fierce efforts to save them. Now, Brandon was nurturing fifteen small, sturdy ones on the top of a grassy hill.

He told me their story. People have been trying for 80 years to create blight resistant chestnuts, and mostly failing. Brandon encountered a man who was having some success, after thirty years of dogged work. He had created a hybrid tree from Asian, native, and European chestnuts.

That man loved those trees and wanted them safe. He was no longer young, and although he did not want to part with the chestnuts, he donated all of them to Brandon because he saw his devotion to the land. He could see Brandon was creating a sanctuary for every living thing that he would always protect.

The proposed PSEG lines will come directly across this hilltop, and the chestnuts, so carefully planted, and tended, will be clear-cut. As we were taking in this sorrow and horror, Brandon found one tree holding a palm-sized, prickly chestnut, the first one from his new orchard, and a promise of future generations of this once-lost tree.

|

|

The chestnut safely tucked into the side pocket of the gator; Brandon drove along the high edges of this deciduous rainforest valley. He spoke of everything here: paw-paw, highbush cranberry, serviceberry, spicebush, chokeberry, persimmons, an east coast almond, and pecan. Also, basswood, tulip poplar, oak, maple, and native pollinators, sedges, bee balm, black-eyed Susan.

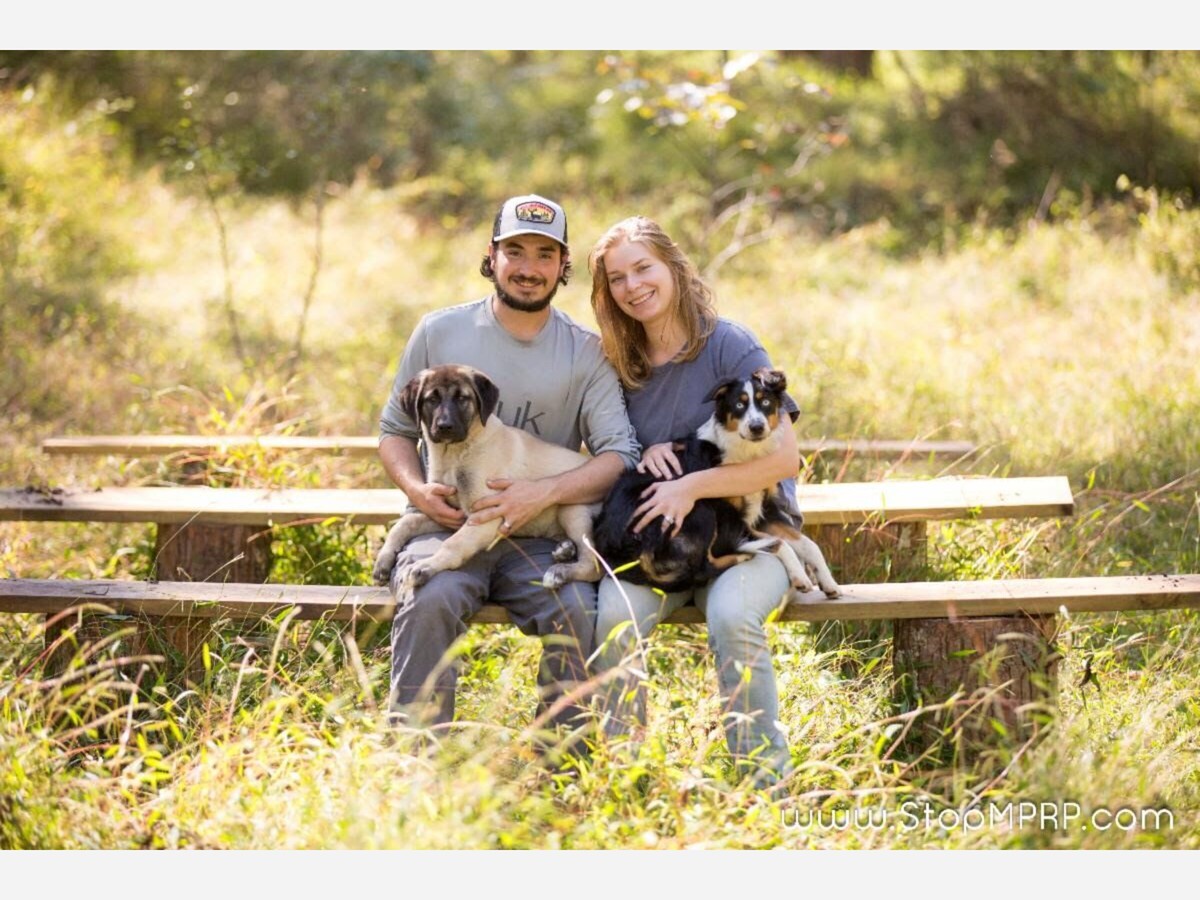

Then Brandon drove me down into a stream valley to a little grove of trees along Ebaugh Creek, to show me where he and Marie had hand-hammered a double row of wooden benches beneath this green canopy. He pointed out the two small trees they had planted for their wedding. They are sending down new roots just where he and Marie stood when they pledged their love before family and friends. They thought they would get to see these trees grow with their marriage. If this battle against PSEG cannot be won, 150-foot H lines will run the length of this rare creek, cold and clean enough to swim with native trout and the endangered darter. The untouched trees all along the creek will be clear-cut, destroying this stream, filling it with silt, sun, and killing every cold-water species in it.

Later in the afternoon, at the kitchen table, sitting with Brandon and his wife, Marie, that spiny chestnut was broken open, and Brandon said, "two good nuts." Those satin-brown, fat, heart-shaped seeds will go into the earth to make another hybrid-hardy tree, a pledge that these lines will be defeated.

|

|

|

Brandon and Marie made the loveliest tea, smoky, sweet, and amber, and we sat across from each other at a long trestle table. They pointed out all they had done, putting in a kitchen, tiling the walls, all of it stopped mid-stream when the news of the PSEG lines came. For the last 3 months they have been dedicating their lives to learning everything they can about MPRP and the cause.

Brandon said, "I have lived here for 30 years, all my life. I have traveled all over the world. I always come back. This is my home. I love the quiet, living in nature, mushroom hunting, a forest, and stream right out my door."

"It fell in my lap. I always wanted a farm. Never believed in traditional farming, always wanted to do something with bio-diversity. You don't need monocrops, but I believe you can use permaculture to create a food forest that will take minimal tending. It will produce a plentiful bounty year after year of flora, fauna, and fungi. I wasn't looking for land, but I heard a farm next to my parents' house was going to auction. I paid off their debt. They gave me the property."

I asked Brandon and Marie how they had met. They smiled at each other and asked, "Have you ever heard of Twitch?" "Nope," I had not. Twitch is a streaming platform that Brandon and Marie spent time on during covid. They spoke for hours, once, 34, talking, sleeping, waking, drawn one to the other.

|

|

|

Marie said that she had grown up in Kiel, a city in the north of Germany, near the Baltic Sea. She lived in a suburban area with trees and parks but didn't have much experience with farms. The first time she came to visit, she stayed for five weeks. One of the first things she said to Brandon was, "It is so dirty here." And he responded, "This isn't city dirt; it's country dirt. Country dirt isn't dirty!"

Brandon said, "The first hour she was here, she knocked the tractor into neutral, and we shot down that hill." which seems like a fair description of their relationship. "We never experienced anything like this relationship before," they said. "There was no doubt."

Soon, Marie said, "I was walking in the woods, hearing the creek, searching for mushrooms." She continued, "The quiet, peaceful land made it easy to make a decision to move here."

Data centers are the hidden and driving reason for PJM and PSEG's demand for power. Marie has a Master's Degree in American Studies on the topic of "The Representation of Artificial Intelligence in Television," and was beginning her doctorate in the same area of study. Both Brandon and Marie can see the benefits of AI, and their ease about their ability to use it for good opened my heart to it a little.

They were clear that AI does not need to use the energy and water that data centers demand. They said, "There are better ways, ways that will not harm the environment to meet the needs of AI. Technology? We love it. We use it. We are against having it destroy the environment and clean water to destroy what everyone needs to live. We believe AI infrastructure can be built properly, considering the environment, citizens' property rights, fresh water supply, and future proof of technology."

We turned to the large, black, upright screen on their trestle table, with an open laptop in front of it. There were scribbled notes about power transmission, in Brandon's quick handwriting scattered around them.

Brandon turned on the monitor and the map of their farm leaped up in front of me, with that broad yellow Z of a line crossing it. I sucked in my breath.

Brandon had driven me up through his fescue fields, and shown me the towering behemoth BGE lines, stalking the next fields on their wide spread steel legs. He knew they were there before he bought his farm. He doesn't like them. He pointed out the clear-cutting that keeps any food supply beneath them sparse and unpredictable. But they aren't going to pick up their hard-toed boots and move onto his land.

|

|

|

But now we could see the perversion. The PSEG yellow line tracked the established black BGE lines, and then at his parents' home, it veered sharply west, taking out their home, then the chestnut field, then it turned south and east, following the length of Ebaugh's cool, native trout stream. And once that yellow line destroyed the place Brandon has called a sanctuary for all his life: his home, his dad's home, and the farms they shared, it rejoined the BGE line and continued south.

Somebody put that line there, someone chose that yellow zag, where it follows the existing line, where it departs. And it was deliberate; someone decided to ravage that particular piece of land.

Brandon was sitting across from me, hip to hip with Marie, because coming to know this enemy, choosing to fight it, has taken half of the table where they share their meals. He said, "It's taking away our future." His next words came out in a rush. "I bought it outright. I thought we were safe here. I can hunt. I can fish. I have plans. We could survive here even if everything…."

He took a soft breath, Marie watching him, "Our future, we thought it was secure. It is always said 'never bet the farm.' I wasn't. I wouldn't. It is hard to find the motivation for anything else now."

"The politicians will answer …" His words are not a threat. They are the task Brandon has taken on, documenting the loss and educating others, especially the elected officials with enough power to stop the lines if they have the will and the courage for that fight.

Brandon has put his business on auto-pilot and is traveling day after day, from northern Baltimore County to the southwest corner of Frederick County, videotaping every affected farmer and property owner who will speak to him. Then he is spending his days and nights creating connections with the people who can turn this fight.

With the time he has left, he studies power transmission, trying to educate himself to combat what is happening to the place he loves. He knows "knowledge is power." He said, "I'm an introvert, but now," and he stopped, "now, along each part of this route, we know somebody."

Sitting across from me, his arms folded across his grey Huk shirt, Brandon's eyes grew wet.

"This is not just a line on paper. People aren't sleeping. They've gone to the hospital. There's high blood pressure. Depression. Divorce."

"You know, before all this started, after supper, I would go up into the fields and plant. Now, it's hard to have the heart for it. Now," he pointed to the computer, the papers around us, "there's this."

He paused and started again, "I wanted to create a place that sustains us, with sustainable foods," that will regenerate again and again without plowing, without pesticides. "An organic food forest," with sustenance at each of its three layers. And once well begun, the land worked "without big equipment." Already he is fertilizing using "the chicken tractor," a rolling blue and white chicken house on wheels with a screened bottom that can be moved across the fields, so he can return nutrients back into the soil.

Then he began to list the species that will be lost if the transmission lines come: "darter fish, brook trout, bald eagles, newts, grey tree frogs; and monarch butterflies, luna moth, hummingbird moth, all pollinators; wild turkeys, box turtles, foxes, great blue heron." And, Brandon added, "the wetlands, the creek, the whole, untouched riparian buffer will be gone." He spoke of "learning what is here, all the herbs the first summer."

Then together, they said, "mushrooms," and he tenderly brought over a "Hapalopilus Croceus," a rare mushroom, that grows out from dead oak trees. It is a "red list endangered species." He said, with sorrow in his voice, "It would take over 200 years to get this mushroom back. The oak tree must grow and die, then the white rot decomposers like chicken of the woods and hen of the woods come in. Then after they have done their job the brown rot decomposers come in like Hapalopilus Croceus. You can't mitigate 200 years of growth by planting sapling trees, and worse, the same type of saplings, all Douglas fir, all white pine. They aren't pest or disease-resistant. Diversity and succession trees; that is how earth systems work."

|

|

|

And, he added, still speaking of what would be lost, "My sanity. I don't want to move. I chose to live here; this place has been my sanctity, a safe quiet place to be introspective. This place made me."

Marie spoke, "It happens fast, too. I embraced this land, this life."

Brandon refolded his arms across his grey shirt. "What is here is irreplaceable. When it is gone, it is gone."

He said he had spoken to PJM, the RTO who granted the contract to PSEG to create the 70 miles of transmission lines.

He asked them these three questions:

1. What is the exact goal of this line?

2. What alternatives were looked at?

3. What is the true reason transmission lines were the solution?

"Those are the most important questions if they answered them truthfully."

"But they don't answer them."

"I haven't gotten one real answer."

Brandon knows PSEG's game.

He listed four reasons PSEG will be rewarded by pursuing this project:

1. "They are generating the energy."

2. "They are being paid to construct the lines."

3. "They are getting paid by the ratepayer to transmit the energy."

4. "They are gaining land, pristine land, good arable land, high value land, preservation land."

"And they are threatening eminent domain on what all these farmers and communities have been bettering."

I have watched Brandon, slim, slight, straight-standing, dark hair curling at the collar, with a short, slightly unruly beard along his cheeks and chin, ask those questions PJM will not answer. He is asking these questions of others, and they are beginning to ask those questions of themselves.

I am used to seeing Brandon in a Huk tee-shirt and that dirt he likes beneath his nails. But when he shows up in a room filled with busy politicians with clip-boards and agendas, he is dressed in a fresh white shirt, a blue sports jacket, and he is wearing clean boots. He is quiet and soft-spoken, polite, and you can almost feel a little shyness.

But Brandon is fighting for every microbe of his land, because he understands that fine dirt at microbial level. And he is not just fighting for his dad's land, his own land, he is fighting for all the land, all the water, because he knows more than those 70 miles is at stake.

|

|

|

He knows we are at a new tipping point with AI, that it is a global contagion and we must get this right.

And so, he is quiet, but fearless as he speaks to politician after politician.

They are listening—members of the senate, the house of delegates, the PSC, and other political figures. So are many others, after they read the 'fact sheet' Brandon has created on the looming threat of unrestricted AI infrastructure projects like MPRP.

Brandon offers his answers for us to consider. "We must restrict AI data centers because they are the single biggest threat to Maryland's stable power grid. They are the single biggest threat to people's property, the agricultural economy, fresh water, and the environment."

He emphasized, "I am not against technology. I love technology. But are we going to destroy our environment for artificial intelligence? I think we must ask ourselves what is the definition of progress? Is it putting money into the pockets of corporations and greedy men, or is it bettering the experience of being a Human? Isn't that what we should be putting our money and time towards, and what your definition of progress should be?"

Brandon said these words again. "Our environment here on earth is irreplaceable. When it is gone, it is gone."

A postscript: When the final PSEG line was announced on October 18, 2024, most of Brandon's farm and his dad's farm had been spared. Not all, but most, because the decision had been made to follow the BGE route.

We will never know why.

Maybe it was because Brandon spoke for every single landowner and farmer in three counties. Maybe because politicians were listening to him. Maybe PSEG hoped if they threw Brandon back his bone, he would settle in the corner and chew it.

He has not. He will not.

Brandon and Marie Hill do not want what nearly happened to them, to happen to anyone else. Brandon knows every line moved, is a line on another piece of land. Now it is someone else's hardship, heartache, and burden to bear. Someone else's farm or wetland or conservation easement or community. Someone else's place de-valued by half.

Brandon and Marie Hill will not stop speaking up and speaking out until MPRP is utterly defeated.

|

|