Image

The ancient secrets of Virginia’s first and only all-native botanical garden

Quarry Gardens at Schuyler has some of the highest variety of plant species in the U.S.

By Jake Solyst, chesapeakebay.net

To understand the ecological wonders at the Quarry Gardens in Schuyler, Virginia, visitors don’t need to go much farther than the parking lot.

Here, you’ll find a relatively small lot surrounded by dirt parking spaces that is bursting with the kinds of native grasses and flowers that once dominated the landscape. It’s what scientists refer to as savanna remnants—the last remaining fragments of what was once a much larger savanna ecosystem. In the case of Quarry Gardens, that’s the Piedmont Savanna.

“The surviving patches of old ground surface in the parking lot area are a tiny glimpse of one of the rarest and most threatened biomes in the world—the Piedmont Savanna," said Devin Floyd, executive director of Piedmont Discovery Center (PDC), who owns and operates Quarry Gardens.

There are many reasons why the parking lot at Quarry Gardens supports such an impressive array of plants. The first is that the ground has never been plowed due to its rocky conditions and is therefore in a “pre-colonial” state, which has allowed native plants to flourish and kept non-native plants from encroaching. The second is that the soapstone that underlies Quarry Gardens (and much of the Virginia Piedmont) creates a rare soil type known as ultramafic soil that supports an above-average variety of native plants.

A trail at Quarry Gardens takes you down to this abandoned limestone quarry. The garden hosts events that showcase the natural beauty of the area. (Photo by Jake Solyst/Chesapeake Bay Program)

A trail at Quarry Gardens takes you down to this abandoned limestone quarry. The garden hosts events that showcase the natural beauty of the area. (Photo by Jake Solyst/Chesapeake Bay Program) Fritillary butterflies visit butterfly weed.

Fritillary butterflies visit butterfly weed. New Jersey tea is one of the many native plants growing at Quarry Gardens.

New Jersey tea is one of the many native plants growing at Quarry Gardens.Quarry Gardens, which includes a 40-acre botanical garden, 140 surrounding acres and over 950 species of plants and animals, supports a number of these savanna remnants, which Floyd says may have been one of the most species-rich ecosystems in North America. Quarry Gardens has therefore become a tremendous location for plant enthusiasts to visit and for botanists to study these secret habitats.

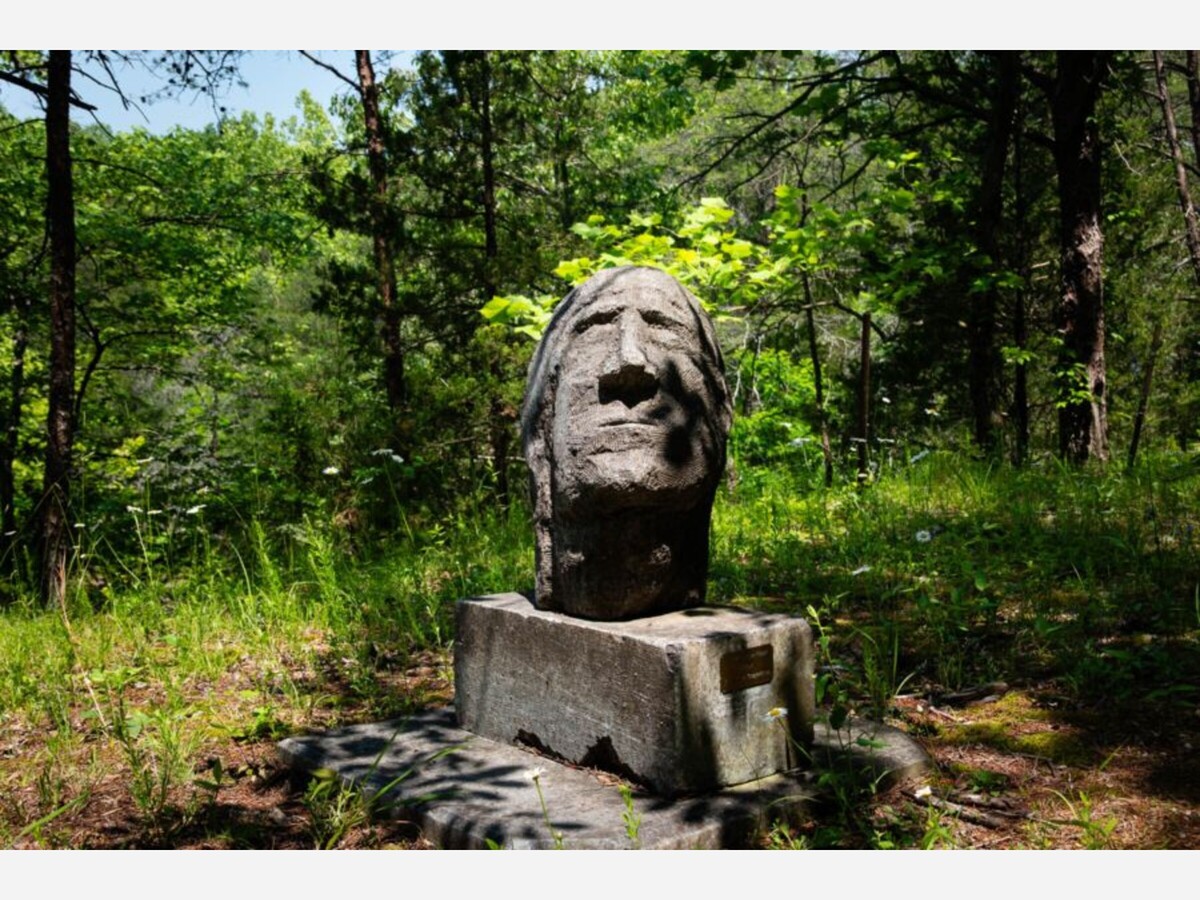

During the early to mid-1900s, Nelson County was a global leader in the quarrying of soapstone, a rock that was used for countertops, sinks, cooking material and other products. However, competition from other nations and technological changes led to a collapse in the local soapstone industry and the abandonment of several quarries.

In the 1990s, Armand and Bernice Thieblot purchased land that hosted several abandoned quarries and eventually came up with the idea of creating a public garden. In 2015, the Thieblots hired PDC to assess the property, refine a master plan to focus only on native plants and ecosystems, and design and create a system of trails, gardens and conservation areas.

PDC now owns and manages Quarry Gardens, which has given them the opportunity to learn more about remnants of the Piedmont Savanna. Through their Piedmont Grassland Assessment project, PDC has demonstrated that there are as many as 40-50 remnant patches of savanna per county in the Piedmont region of Virginia, each one harboring rare and unusual species and very high levels of biodiversity.

“This kind of flips on its head the old romantic notion of rich towering forests hosting the most diversity in plants,” said Floyd.

Brown widelip orchid (Liparis liliifolia) is native to the Eastern United States, particularly the Appalachians, Ozarks, Great Lakes region and the Ohio and Upper Mississippi Valleys.

Brown widelip orchid (Liparis liliifolia) is native to the Eastern United States, particularly the Appalachians, Ozarks, Great Lakes region and the Ohio and Upper Mississippi Valleys.Research conducted by the PDC team and its partners, such as the Southeastern Grasslands Institute, hypothesize that plants found in remnant patches have ancient root systems and are dependent upon the natural disturbances that shaped their evolution, including fire and grazing herbivores such as bison. To simulate wildfires, conservation groups conduct controlled burns that stimulate new growth and improve the health of the soil.

The research at Quarry Gardens is giving homeowners, landscapers and conservationists the knowledge they need to protect or restore places that might be harboring savanna remnants. For example, many surviving remnants require a lot of sunlight and limited tree canopy, but landowners who are unaware that they have a remnant patch on their property could be tempted to grow a forest, which would block out sunlight and keep all those diverse native plants from emerging. Even worse, landowners may mistake rare natives for weeds and suppress them with harmful herbicide or development.

A trail at Quarry Gardens takes visitors around a lake near the abandoned quarries. (Photo by Jake Solyst/Chesapeake Bay Program)

A trail at Quarry Gardens takes visitors around a lake near the abandoned quarries. (Photo by Jake Solyst/Chesapeake Bay Program)“It is critical that we find these amazing time capsules, help people learn to see them and then figure out how to protect them,” said Floyd. “Not only do they host some of the most amazing diversity in all of North America, they also provide the seeds and the logic for how to restore degraded landscapes.”

Quarry Gardens is open during events and by reservation but plans to soon be open to the public more often. The botanical garden boasts two miles of walking trails, multiple native plant gardens, a visitor center that includes exhibits on native plants, local ecosystems and the history of the soapstone industry in Schuyler, as well as a classroom and research laboratory.

Students, hikers, birders and plant enthusiasts are sure to get a lot out of a trip to Quarry Gardens. It will also continue to be a place of important conservation and research for scientists to learn more about the Piedmont region’s ecological secrets.

“This place really pulls at my heartstrings because there’s always something new to find,” said Floyd.

Jake has been telling environmental stories about the Chesapeake Bay watershed for nearly five years. Having spent a decade in Baltimore, Jake now resides in Charlottesville, Virginia where water flows to the Bay via the James River watershed.

View all stories by this author