Image

Chesapeake Bay health downgraded to a ‘C’ in this year’s report card

A revised bay agreement is coming, while more federal cuts loom large

Heath Kelsey of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science speaks at the release of the 2025 Chesapeake Bay report card, which gave the estuary a "C" grade. (Photo by Christine Condon/Maryland Matters)

Last year’s weather didn’t treat the Chesapeake Bay too kindly, if you ask Bill Dennison.

“It was too wet, and then it was too dry — and always too hot,” said Dennison, the vice president for science application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.

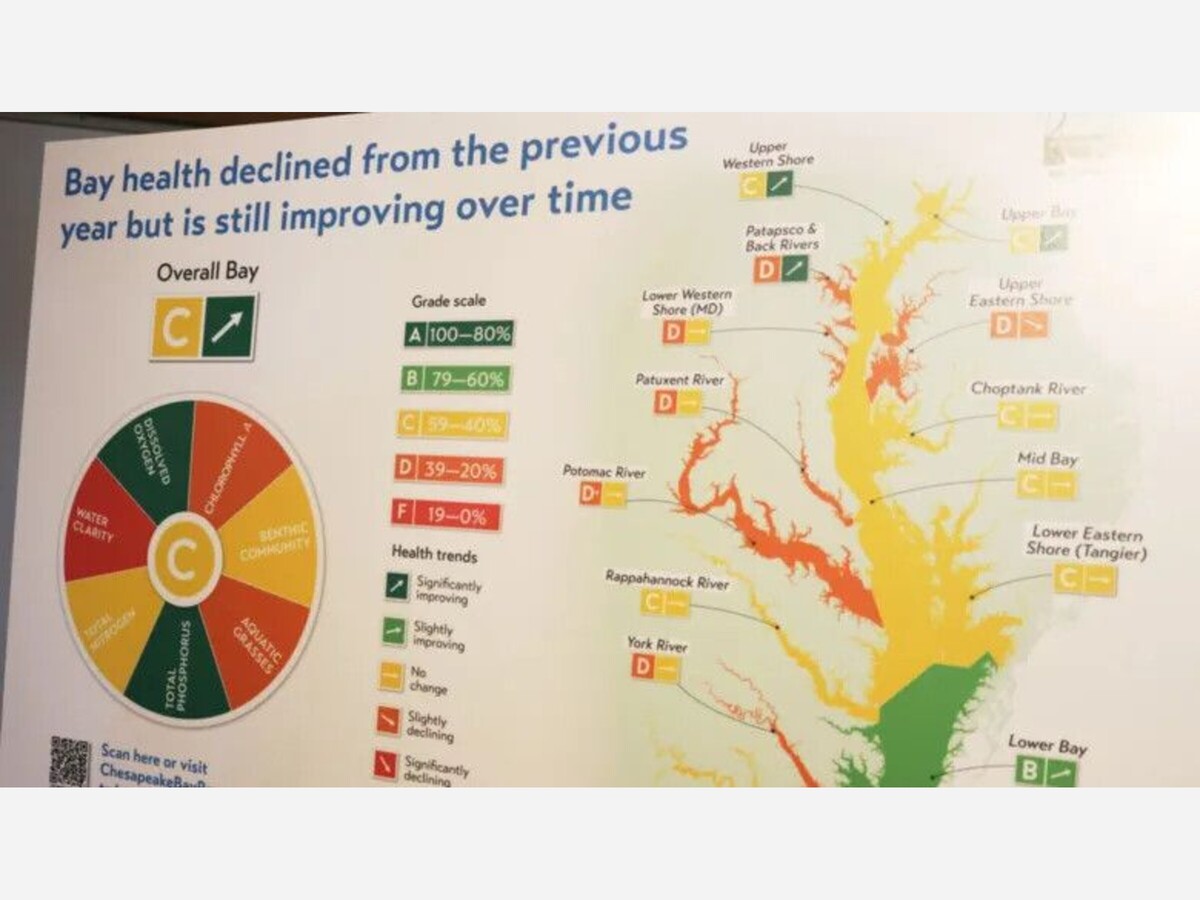

Those conditions are part of the reason the bay got a “C” on this year’s UMCES report card, down from last year’s all-time high grade of “C+.”

“The crops didn’t have enough water, so they were not soaking up nutrients,” Dennison said at Tuesday’s release of the report card. “So when it did rain, there were excess nutrients washing into the bay.”

A number of factors contribute to the score, including measurements of aquatic grass growth, water clarity, and harmful nutrients nitrogen and phosphorus, which run off from fertilizers and sewage treatment plants, among other sources. Excess nutrents spur the growth of algae, which suck oxygen from the water as they die, creating “dead zones” that kill off underwater life.

Though this year’s score dropped, Dennison and others were quick to point out that the overall trajectory of the bay is more positive. Of 15 bay regions identified in the report only one has seen a declining trend dating back to the 1980s: the Upper Eastern Shore, which includes the Chester River. Six regions are improving, including Baltimore’s Back and Patapsco rivers, and the rest are holding steady, said Heath Kelsey, director of the Integration and Application Network at UMCES.

Kelsey said the bay has faced “lots of development, lots of population moving in, lots more traffic and impervious surface — and climate change is adding to that, too. But nevertheless, over time, whatever we’re doing is making a difference.”

The view from the Annapolis Maritime Museum, which hosted Tuesday’s unveiling of the latest Chesapeake Bay report card. (Photo by Christine Condon/ Maryland Matters)

The view from the Annapolis Maritime Museum, which hosted Tuesday’s unveiling of the latest Chesapeake Bay report card. (Photo by Christine Condon/ Maryland Matters)

Yet bay states have fallen short of their 2014 pledges for nutrient reduction: By 2024, according to computer models, nitrogen reduction hit 59% of the goal and phosphorous reduction achieved 92% in the six states, plus Washington, D.C., in the bay watershed. They did meet other goals by that year, including reduced sediment runoff.

Early gains came, in part, from outfitting wastewater treatment plants with enhanced technology so they discharge fewer nutrients. But slowing pollution from what are known as “non-point” sources, such as stormwater runoff from cities and farm fields alike, has been more difficult.

The bay has also responded to the estimated reductions more slowly than expected. From 1985 to 1987, 26.5% of the bay’s tidal waters met water quality standards, according to ChesapeakeProgress, an online resource from the Chesapeake Bay Program. In the most recent assessment, between 2020 and 2022, 29.8% of the bay met those same standards. The numbers have declined steadily since a high point of 42.2% from 2015 to 2017.

A 2023 report from the Bay Program’s Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee laid out some reasons for the slow improvement. Computer modeling could be overestimating nutrient reductions, the report said. It also called for increased adoption of non-point pollution reduction measures, and urged governments to consider programs that reward farmers and other landowners based on the success of conservation practices, rather than awarding funds to implement a practice, regardless of the pollution-reduction outcome.

Officials have been drafting a revised bay agreement, with new goals for the states, that could be released for public comment next month, pending a vote from a Chesapeake Bay Program committee.

Meanwhile, cuts — some proposed and others realized — to federal agencies by the Trump administration are adding fresh uncertainty to bay restoration efforts.

Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Maryland), who appeared via video for Tuesday’s event, said Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lee Zeldin publicly assured him that cuts would not be proposed for the Chesapeake Bay Program, the EPA-led office that leads the bay cleanup effort.

It’s a change from Trump’s first administration, when the president repeatedly proposed cutting the Bay Program’s funding, or zeroing it out altogether, though he was denied by Congress.

“That’s good news, but we know that that’s not the only program important to the health of the bay, which is why we’ll push back against the administration’s efforts to cut other key environmental programs,” Van Hollen said.

Bill Dennison, of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, speaks at the release of the 2025 Chesapeake Bay report card. The bay got a “C” this year. (Photo by Christine Condon/Maryland Matters)

Bill Dennison, of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, speaks at the release of the 2025 Chesapeake Bay report card. The bay got a “C” this year. (Photo by Christine Condon/Maryland Matters)

President Donald Trump’s proposed budget would slash billions from the EPA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. Geological Survey and the Department of Agriculture, potentially hampering funding for improvements at sewage treatment plants, scientists that study bay wildlife and programs that assist farmers with conservation practices, according to a May news release from the Chesapeake Bay Foundation.

“It’s chaos on the hour,” Bay Foundation President and CEO Hilary Harp Falk said Tuesday. “We have seen some slightly positive news in the EPA Chesapeake Bay Program getting full funding in the president’s proposed budget, but what we’re also seeing is major cuts to NOAA and major cuts to USGS, including bedrock scientific programs.

“You can’t just pull half of those federal agencies out and expect to have results,” she said.

To Dennison, some of the biggest changes so far have been departures of senior USGS scientists, who focused on monitoring conditions in the bay watershed. Some of them opted for the early retirement plan offered by the administration in order to thin the federal bureaucracy, Dennison said.

At UMCES, officials are also concerned about Trump administration attempts to limit the amount of grant funding that universities can use for overhead, Dennison said.

“We’re doing a lot of the doomsday list-making,” he said, but added that the institution is also trying to keep a level head.

“I think it’s important not to freak out,” Dennison said. “Let’s keep our head down, doing good work. And then, when we’re really confronted with the challenge, we’ll deal with it. But for right now, what we hear is being proposed doesn’t often end up being the reality.”

Despite tough state budget conditions, Maryland officials are trying to plug holes left by the federal government, said Maryland Natural Resources Secretary Josh Kurtz.

In remarks on Tuesday, Kurtz cited the recently passed Chesapeake Legacy Act, which will, in part, let DNR incorporate water quality data collected by community groups such as riverkeepers — potentially filling in gaps caused by federal cuts.

That bill may have been aided by its small price tag: It allocates about $500,000 for a new certification program for conservation-minded farmers.

Maryland Natural Resources Secretary Josh Kurtz at the release of the 2025 Chesapeake Bay report card from the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. (Photo by Christine Condon/Maryland Matters)

Maryland Natural Resources Secretary Josh Kurtz at the release of the 2025 Chesapeake Bay report card from the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. (Photo by Christine Condon/Maryland Matters)

Kurtz also cited a 2024 law, the Whole Watershed Act, which funds targeted water quality assistance for five communities.

“Where there are things that we’re going to lose, I think we are well-positioned as a state because of the strength of the partnership, to be able to keep that scientific understanding going,” Kurtz said.

Dennison said scientists at UMCES have been zeroing in on the Upper Shore, the only region with a declining water quality trend in the center’s report card.

He said the problem is a bit of an “enigma” in an area where a solid number of farmers are using cover crops to prevent erosion between growing seasons, and a significant amount of nutrient-laden poultry litter from area chicken houses is trucked to the Western Shore instead of being spread as fertilizer to Eastern Shore farm fields.

Scientists have a few hypotheses, including that the Upper Shore’s flat elevatio could cause the slow groundwater circulation in the area, which could be delaying observations of progress.

“We’ve put into practice some of these things that we’re seeing positive responses to elsewhere, but they’re slower on the Eastern Shore because it’s such a flat [area with] poorly drained soils. It’s just taken a while for that to happen,” Dennison said.

He said the center will host a series of workshops on the Shore later this month, in collaboration with the Delmarva Land and Litter Collaborative, focused on environmental practices in chicken houses, bringing in farmers and poultry companies.

“We don’t really understand why it’s uniquely degraded, whereas everywhere else in the bay is holding steady or improving, so we’re trying to get at that, but we’re doing it in partnership with the farming community,” Dennison said.