Image

Once-abundant black ducks make a case for saving habitat

By: Alonso Abugattas, Bay Journal

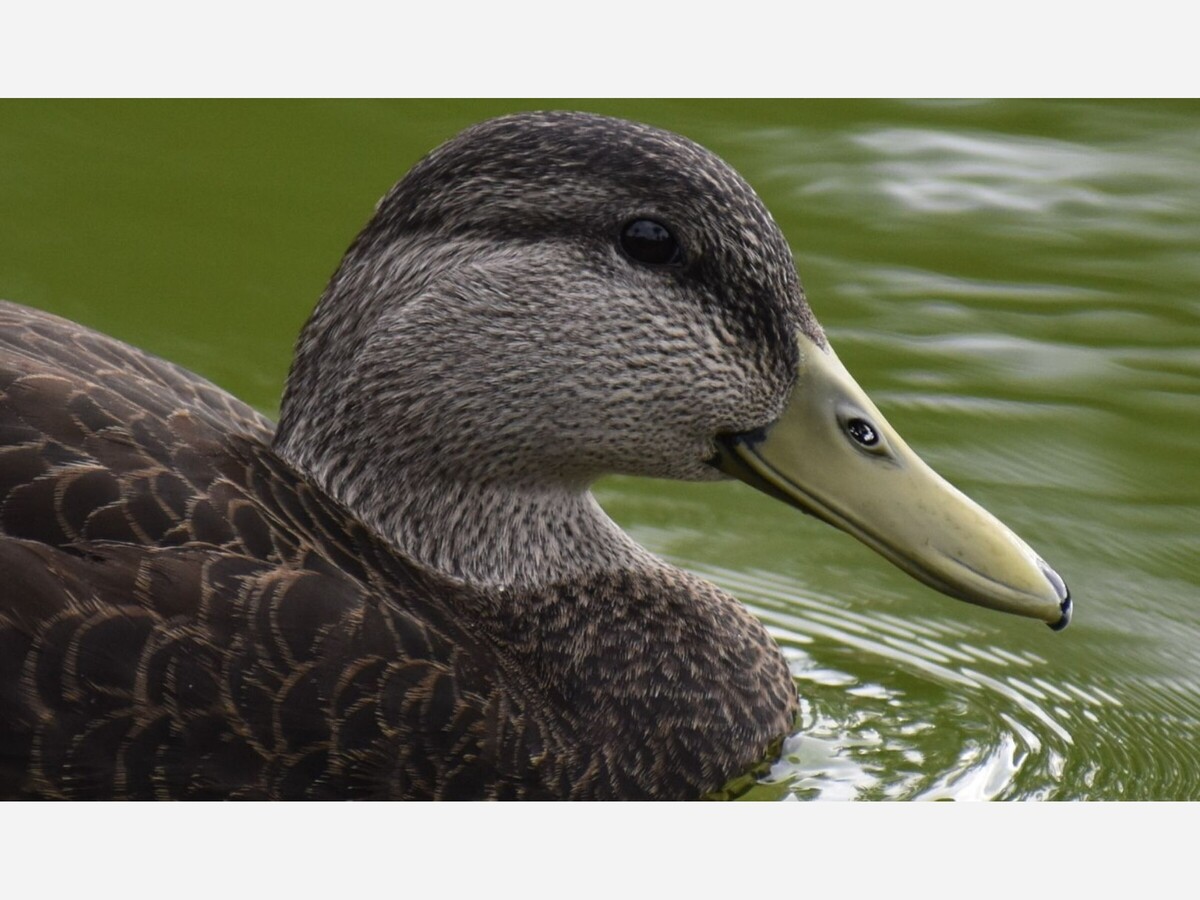

This male American black duck was photographed during breeding season in Newfoundland. (Alan Schmierer/public domain)

The story of the American black duck over the last century or so is complicated. Black ducks used to be one of the most abundant breeding ducks in the U.S., mostly in the upper Midwest and Northeast. The majority now nest and breed in Canada, as far north as the shores of Hudson Bay from late May to mid-July.

Here in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, we’re far more likely to see them in the winter through early spring — though, as with many waterfowl, there are some year-rounders this far south.

Today the American black duck (Anas rubripes), although still possibly declining in some parts of its breeding and wintering habitat, is considered a species of least concern, with an estimated breeding population in 2023 of 732,000, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

But the 20th century was not kind to A. rubripes, which likely numbered in the millions in previous centuries. Historical population estimates, and even modern ones, vary widely, but there is general agreement that the species declined by well over 50% between the early 1950s and early 1980s, when strict hunting controls were enacted.

Hunting is thought to have been the main factor. The black duck is an extremely popular game bird for both its elusiveness and culinary appeal.

An American black duck takes flight, likely a female because of the duller-colored bill. (Henry T. McLin/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

But there were other pressures too, notably loss of wetland habitat throughout its range. Pesticides took a toll as well; A. rubripes was not spared the ravages of DDT, which weakened the eggshells of countless bird species.

And there was — and still is — competition from the common mallard duck, one of its closest relatives. Previously, the two species had mostly separate breeding and wintering grounds. But habitat loss is less detrimental to the more adaptable mallards, which not only outcompeted the black ducks but also crossbreeds with them.

Mallard males are known for ganging up on and forcibly mating with females — not just with their own kind, but with other species and black ducks in particular. An estimated 4% of the breeding American black ducks are mallard hybrids, a percentage that might be higher if it weren’t for a tendency, according to a study of captive ducks, for female hybrids to die in their first year, before reaching sexual maturity.

Except for a yellow bill on the male and a dull olive bill on the female, black duck sexes look very similar — like a darker-than-usual version of the female mallard in the body, with a contrasting pale brown head and neck with a dark crown. On the ground, their most notable difference from the female mallard is their violet-colored speculum (a patch of contrasting color on the secondary wing feathers), bordered in black, compared with the mallard’s blue-purple speculum, bordered in white.

The male black duck can look like a slightly darker than normal version of a female mallard. The giveaway is its violet wing patch, which is closer to blue and bordered in white on the mallard. (Mark Nenadov/CC BY 2.0)

Black ducks form pairs over the winter, well before heading north to their breeding grounds. There, the hen builds a nest, usually on the ground of elevated hummocks and the dry edges of wetlands.

She lays 6–12 cream or greenish-buff eggs, which she incubates for 26 to 29 days. All of the young hatch within a few hours and are ready in a few more hours to follow the mother, usually at night, to marshy edges. There, the ducklings feed almost exclusively on larval and adult invertebrates, particularly in the first few weeks.

The young fledge at about two months and are ready to head south with the grownups by fall.

They are usually sexually mature the next season. Black ducks have only one brood per year and show remarkable nest fidelity, often returning to within a few yards of where they nested the year before. Barring disease and predation, these birds can live 20 or more years; the oldest American black duck on record lived 26 years and 5 months. It was banded in Pennsylvania in the early 1950s and recovered in 1978 in Delaware.

The American black duck’s diet varies widely, depending on both season and habitat, according to Cornell. “Animal foods are essential during pre-laying and laying stages,” according to the bird’s profile in Cornell’s online resource, Birds of the World. The adults eat mayflies, caddis flies, dragonflies and true flies, as well as snails and clams, supplementing this high-protein diet with the seeds of bur reed, sedges, rice cut-grass and pondweed. Although they are dabbling ducks, they can dive 12 feet or more to get food. Sometimes, they even feed at night.

In 2016, the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture named the American black duck one of three “flagship” species — along with the saltmarsh sparrow and black rail — most in need of saltmarsh habit restoration and preservation.

The group’s Black Duck Conservation Plan calls for “restoring and enhancing” about 400,000 acres of the birds’ wintering habitat and protecting existing high-quality habitat. The 2023 population estimate of 732,000, referred to earlier, is an 8% increase from the year before. So, if last year is an indication of their future, American black ducks appear be holding their own, despite all of the threats they face. Let’s hope the trend continues.

Alonso Abugattas, a storyteller and blogger known as the Capital Naturalist, is the natural resources manager for Arlington County (VA) Parks and Recreation. You can follow him on the Capital Naturalist Facebook page and read his blog at capitalnaturalist.blogspot.com.