Image

When Isaac Tyson Jr. looked out across the sparsely vegetated hills in the serpentine barrens of Baltimore County 200 years ago, he saw something others didn’t see, because he knew something others didn’t know.

Underground, the land was far from barren. It contained a mineral that would make Maryland a leader in 19th century industry, a key ingredient in the steel in our nation’s buildings, bridges and railroads.

The mineral was chromite – which this year was recognized as Maryland’s state mineral for its central role in state history.

Tyson discovered chromite in Maryland at some point between 1808 and 1827. He recognized that chromite always occurred in the serpentine. By following the barren landscape, he could follow the chromite. Chromite contains chromium, a shiny element used to strengthen alloys and make high-grade steel through the production of ferrochrome. It’s found abundantly in Baltimore, Harford, Howard and Montgomery counties.

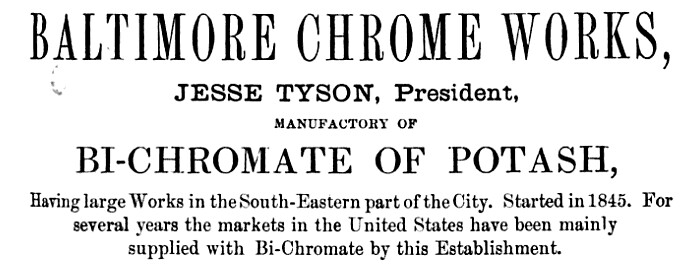

In the decade following his discovery, Tyson took chromite mined from Bare Hills and Solider’s Delight and processed it at his Baltimore Chrome Works, making the state the chrome-processing center of the world. In fact, Maryland was the primary and sometimes sole source of chromite during the post-colonial industrialization period.

Chromite has not been found at Soldier’s Delight since World War II. Please remain on hiking trails if you visit Soldier’s Delight – never walk off path, which can damage sensitive natural resources.

Chromite is heavy, opaque, iron- to brown-black in color, with a pitchy luster, uneven fracture and hardness nearly that of steel.

During the General Assembly this spring, State Geologist Stephen VanRyswick testified in front of the House Health and Government Operations, and Senate Education, Energy, and the Environment Committees, providing information in support of making chromite the official state mineral. The Maryland General Assembly approved the measure.

A piece of chromite in a display case at the Maryland Geological Survey in Baltimore.

“Without chromite, the development of steel would not have been as advanced in this nation,” VanRyswick told lawmakers.

Mining ramped down in the 1860s as better sources of chromite were found across the globe. Processing continued at Baltimore Chrome Works until 1985. After an investigation revealed large amounts of chromium seeping into the harbor and groundwater, the owner of the plant entered a consent decree with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Maryland Department of Environment in 1989.

A 10-year, $110 million cleanup effort was completed in 1999, funded fully by AlliedSignal, then owner of the Chrome Works. The area is now redeveloped and called Harbor Point.

Virginia pine started to take over the Soldier’s Delight area in the 1930s due to a lack of wild fire. In the 1980s, Maryland Department of Natural Resources started removing the pines and re-established a serpentine ecosystem on the land, maintained through prescribed fires.

Today, Soldier’s Delight in Baltimore County is a Natural Environment Area.

If you want to learn more about chromite at Soldier’s Delight, consider attending a tour led by retired geologist and Maryland Park Service volunteer Johnny Johnsson. Johnsson has been exploring Soldier’s Delight for more than 30 years and is an expert on the area. You can check for future tours on the Patapsco Valley State Park events page.

You can also check out a giant hunk of chromite at the Exhibit Hall, along with a photo of David Shore, the young man who championed making chromite the state mineral.

Chromium is still used to strengthen metals today. South Africa is now the largest producer of chromite ore in the world.